When boxing is declared nearly dead, as has been the case many times over the last 70 years, many observers point out that it always finds a way to stay relevant. This may still be true in many parts of the world, but there can be no question that boxing is in a steep decline in the United States in terms of cultural importance. Most diehard boxing fans who aren’t involved in the boxing industry understand that they are virtually alone in their love of the sport. When we go to work or socialize, we’ll hear many conversations about the local NFL, NBA, or college team. But almost nobody can name 5 professional boxers who have had a match in the last year. Boxing talk around the water cooler mostly revolves around Jake Paul, Mike Tyson, Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Leonard, or Floyd Mayweather.

It’s no great surprise that Congress was successfully lobbied into considering something called the Muhammad Ali American Boxing Revival Act. The sport appears to need reviving in America. In this article, we aren’t going to explore the reasons for the decline; that topic has been written about and discussed ad nauseam by far better writers and observers. We will simply focus on analyzing how the sport has been presented over the last 25 years to contextualize the current state of boxing in America and how we got here. We have segmented this period into 4 eras that we’ll briefly summarize before we get into the data. Many readers probably know this material better than we do, so feel free to skip ahead to the pictures.

HBO Dominance Era (2002-2014)

Our data sample begins in 2002, when HBO was well into its second decade of dominance. During this period, promoters would market individual cards to the networks and sell them to the highest bidder. Showtime was HBO’s only competition for high-end boxing matches and it was at a significant budget disadvantage. In 2002, there were 106.7 television households in the USA. HBO had 26 million subscribers, Showtime had 13.3 million. Viewership was quite strong compared to today, with Lennox Lewis-Vitali Klitschko drawing 4.6 million viewers on HBO in 2003.

Seven different promoters had at least 30 cards on either HBO or Showtime during this era: Top Rank, Don King, Golden Boy, Goossen, Main Events, Gary Shaw, and DiBella. All of them promoted shows on both networks, and there were many co-promotions with multiple promoters involved. The HBO-Showtime rivalry was often written about in these years, though in reality, HBO’s dominance was never truly threatened.

Viewership was in decline throughout this era, even as HBO had grown to 28.6 million subscribers by 2010 and Showtime had grown to 22 million subscribers by 2013, which was also the year that Netflix surpassed HBO in subscribers – a harbinger of the sweeping transformation of the entire industry within the next decade. There were many articles written about HBO’s need to change things, as they were overpaying for fights and bidding against themselves.

In 2007, Golden Boy, which had grown to become one of the top two promoters alongside Top Rank, signed an exclusive output deal with HBO. This began to change the dynamic for the networks and promoters alike. At the end of Golden Boy’s HBO deal in 2011, Ken Hershman made the jump from Showtime to HBO. Stephen Espinoza, formerly a lawyer for Golden Boy, was hired by Showtime to replace Hershman. In 2012, Showtime aired 11 Golden Boy shows, equalling the total they had aired from 2002-2011. Hershman ripped the band-aid off by announcing in 2013 that HBO would no longer work with Golden Boy. At this point, it seemed that HBO would be anchored by Top Rank, while Showtime would be anchored by Golden Boy, and there was more parity between the two broadcasters than there had ever been. Floyd Mayweather moved to Showtime in 2013, further amplifying the rivalry.

And then, in the midst of ongoing disagreements with Oscar De La Hoya in the summer of 2014, Richard Schaefer left Golden Boy Promotions and threw everything into disarray. This coincided with fighters often thanking Al Haymon in the ring after fights in recent years. Golden Boy sued Schaefer and ended up surrendering promotional rights to several fighters in the settlement of the lawsuit. And that brought HBO’s era of dominance to an end.

Premier Boxing Champions Era (2015-2017)

Al Haymon launched his ambitious attempt to control the boxing market early in 2015. His approach was to buy time on multiple networks while acting as an advisor, not a promoter. He partnered with an assemblage of mid-tier promoters – Warriors, DiBella, Mayweather, Goossen (TGB) among them – and placed his advisees on their cards. Haymon locked up time on NBC, Spike, CBS, Bounce, ESPN, and FS1. The venture was backed by a $425 million investment from Waddell and Reed, an investment firm. There was early confirmation that the industry was threatened by the move, as Golden Boy and then Top Rank sued PBC, alleging Ali Act violations.

The big story was the return to the wider audiences of broadcast networks, which had given up on boxing in the late 90’s after HBO’s overspending made it unprofitable. The early returns were good, with 3.37 million viewers tuning in to the first show. But the viewership cratered throughout 2015, and 2016 delivered the most dismal boxing schedule in years.

Top Rank and Golden Boy featured on HBO in 2015-2016, with Showtime mostly leaning on PBC. HBO’s ratings in this period showed a slight rebound from previous years for big events, but were still in a general decline through 2017.

Top Rank settled its lawsuit with PBC in 2016, and Golden Boy’s lawsuit was dismissed in 2017. But Haymon’s gambit had largely run its course by late 2016 when the time buys on broadcast television ended. PBC operated primarily on Showtime in 2017, while ESPN decided to upgrade to world-level boxing for the first time by agreeing to a 4-year exclusive deal with Top Rank.

Investment Boom Era (2018-2024)

With the broadcast network experiment over and HBO obviously crippled, the battle to be the next dominant force on the American boxing scene was on. The opening salvo came in May 2018 when Eddie Hearn and upstart DAZN announced an 8-year, $1 billion deal for 32 events a year in both the U.S. and U.K. to be broadcast entirely on a subscription streaming service. DAZN followed that up by locking up the second season of the World Boxing Super Series in July. Canelo Alvarez and Golden Boy signed with DAZN in October, with Alvarez securing a 5-year, 11-fight deal for $365 million. Gennady Golovkin signed a 3-year, 6-fight deal with DAZN in March 2019, which was widely viewed as a sign that Alvarez-Golovkin 3 was imminent.

Then, Top Rank signed a 7-year deal with ESPN in August 2018 that called for 54 shows a year, many of them airing on the fledgling ESPN+ streaming service. The deal also gave Top Rank full responsibility for managing international content with other promoters.

Finally, PBC signed a 3-year deal with Showtime in August 2018 and a 4-year deal with Fox in September 2018.

Each platform had a power promoter, a major heavyweight, and a business model they felt gave them an advantage. Showtime was leaning on a legacy of top-level production and a boxing brand on a known linear platform. ESPN had by far the greatest reach and was the top sports broadcasting brand of the last 30 years in America, and they were seemingly at the forefront of linear networks launching streaming services to remain relevant. DAZN was backed by multi-billionaire Len Blavatnik. The American launch was just one market for a first-of-its-kind global sports streaming service. And they had the biggest cash cow in boxing, Canelo Alvarez, on their air.

HBO announced in September 2018 that it was getting out of the boxing business at the end of the year, ending a 45- year run as the biggest player in the sport. The last show was seen by a paltry 339,000 viewers, encapsulating the entire industry’s fall over the preceding decade.

Every platform was seriously tested by the pandemic in 2020, but DAZN was thought to have been the most affected. To make matters worse, Canelo sued Golden Boy and DAZN for breach of contract in September 2020, just 3 fights into his 11-fight deal. DAZN was widely believed to be in trouble. But Eddie Hearn patched things up and kept Canelo in the DAZN fold for a while longer.

The pandemic fundamentally changed the American boxing market for several years, and as some of the contracts signed in the spending spree of 2018 started to mature in 2022, the picture started to become clearer about which platforms were throwing in the towel and which were in it for the long haul. Golden Boy extended its deal with DAZN in May 2022, while Fox chose to let its deal with PBC lapse at the end of 2022. While rumors swirled about Showtime’s future in boxing, Matchroom inked a 3-year extension with DAZN in May 2023. Jake Paul’s Most Valuable Promotions also signed on with DAZN in May 2023 and expanded the deal in October.

Showtime ultimately announced in October 2023 that it would air its last boxing broadcast in late 2023, ending a 37-year run. PBC wasn’t out of commission long, as they secured a deal with Prime. Sources suggested the pact would deliver 12-14 shows a year beginning in March 2024, though it has produced just 11 shows in 22 months to date.

Riyadh Season, which had already aired 6 blockbuster cards on DAZN, partnered with them exclusively in a multi-year deal announced in October 2024.

And then in November 2024, Queensberry, and its loaded heavyweight stable, signed a multi-year exclusive agreement with DAZN, set to begin in April 2025.

DAZN Dominance Era (2025-)

DAZN had ramped up its output in 2024, delivering 141 professional boxing cards (not counting influencer cards and bare knuckle boxing). In February 2025, DAZN built on its relationship with the Saudis by selling a $1 billion stake to the Saudi sovereign wealth fund.

In July 2025, the last domino fell when ESPN didn’t renew its 7-year relationship with Top Rank.

As 2026 begins, the only American competitors to DAZN are ProBox and the new Zuffa Boxing product on Paramount+. All the linear broadcasters have fallen by the wayside, and most of the big streaming platforms have declined to commit to regular boxing programming.

Our Methodology

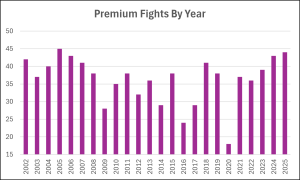

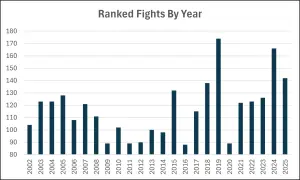

For our research, we logged two categories of bouts using the annual year-end Ring Ratings: Premium fights and Ranked fights. Ranked fights involve at least one ranked fighter. Premium fights are a subset of Ranked fights that pit two ranked fighters against each other. We chose these two categories to reflect the most valuable bouts in the marketplace.

We chose to use the Ring Ratings out of convenience because we can track them through history and compare years and networks by how often matches were made between fighters ranked in the top 10 of any division. But we admit it’s an imperfect proxy. Some divisions had 11 fighters ranked if a Ring champion had been crowned. Some world-class fighters fell out of the rankings due to inactivity, and their fights were not included here, even though they were widely viewed as being among the best fighters in the world. Some fighters were ranked in one weight class but moved up or down in weight and fought in a different weight class. We made the decision to include those fights in our scoring system.

We settled on using the year end-rankings for the subsequent 12 months of action. The annual fighter rankings are helpfully archived by Boxrec here. We used the annual year-end rankings only and many fighters may have taken a loss (or scored a big victory) that moved them in or out of the rankings in the months that followed the year-end rankings. Consequently, there were some fights included or excluded that might seem counterintuitive, but we didn’t note a consistent pattern of under- or over- representation in any years. In other words, the system may have some flaws, but it is applied equally across each year. Lastly, Ring magazine has been owned by both Oscar De La Hoya and Turki Al-Sheikh in recent years, and many may question whether that has influenced the rankings. But it’s the only ratings archive that we are aware of that covers the whole period we are studying: 2002 to 2025.

32 platforms have broadcast at least one Ranked boxing match since 2002: HBO, Showtime, ESPN, DAZN, Prime, Fox, Fox Sports Net, Telefutura/Unimas, Versus/OLN, Telemundo, NBC Sports Net, EPIX, AWE/Wealth Net, Estrella, NBC, CBS, Spike, Bein Sports, FS1, UFC Fight Pass, ProBox, Peacock, Triller+, Netflix, TyC Sports, Bounce, Fubo Sports, Audience, TruTV, BET, Top Rank Fast Channel, and independent PPVs. Interestingly, every night of the week has hosted a boxing series at some point in the last 24 years. We’ve seen series that focused on prospects. We’ve seen series that tried to incorporate music. We’ve seen a few tournament formats. We’ve seen a reality-based series. We’ve seen international broadcasts and series broadcast in Spanish. We’ve seen boxing broadcast on sports platforms, and also on platforms that have nothing to do with sports or boxing. A lot has been attempted in the realm of boxing broadcasting in America.

Our aim is to identify trends and provide context for the current boxing broadcasting market in America.

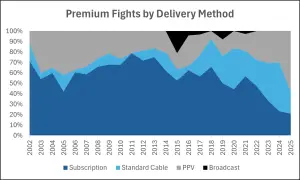

Premium and Ranked Fights

In the early HBO dominance years, when promoters weren’t siloed with exclusive output deals, Premium fights were more commonplace. The most powerful platform had a lot of leverage over promoters, who were fighting over a limited number of dates and had to provide the most lucrative matches they could. Once Golden Boy signed an output deal in 2007, Premium fights started a decade-long decline as platforms increasingly began relying on a single promoter, and the leverage shifted more to the promoters. The low point was 2016, when HBO was in rapid decline and the PBC time buys were expiring. The investment phase, beginning in 2018, ramped Premium fight output up as the cash influx and intense competition made bigger fights more important. The current situation resembles the early 2000s, with one platform clearly holding much more leverage than anyone else in the market.

We see a similar pattern in Ranked fights except the PBC era resulted in an immediate boom for Ranked fights that quickly lost steam. The investment boom era led to a significant increase in Ranked fights, mostly due to so many more fights and undercards being aired on streaming platforms with no programming constraints.

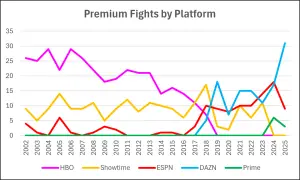

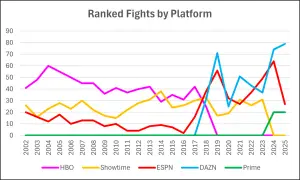

Next, we’ll take a look at Premium fights that aired on the five most prominent platforms of the last 24 years: HBO, Showtime, ESPN, DAZN, and Prime. We are including all tiers and channels of each platform as one entity. For example, the HBO family includes HBO, HBO Latino, HBO PPV, and HBO2.

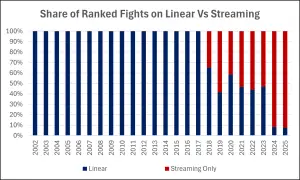

HBO dominated the landscape every year from 2002 to 2016. Showtime led the way in 2018 when HBO got out of the boxing business. ESPN led in 2020, 2023, and 2024 behind the strength of the Top Rank relationship. DAZN has led in 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2025. But DAZN has strengthened its position so much that it broadcast more premium fights in 2025 than HBO ever did during its stretch of dominance. The same relationship holds for Ranked fights, but the effect is even more pronounced.

Market Share By Platform

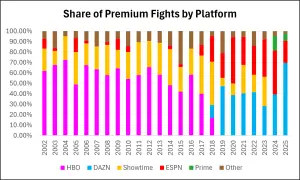

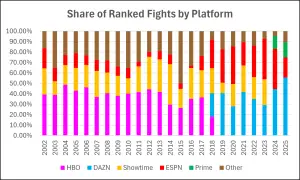

We can see HBO’s dominance right up until 2014, when Showtime started to pull closer in Premium fights. The PBC era really weakened HBO in terms of Ranked fights and seemingly left them handicapped and unwilling to match the big investments that came in 2018. ESPN was a real rival to DAZN throughout the last 7 years, but its exit in 2025 left DAZN with a stronger share of Premium fights in any year except HBO in 2004. And DAZN in 2025 was the only platform in the sample size to garner more than 50% of the market share of Ranked fights.

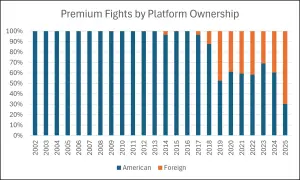

2025 was also the only time that foreign-owned platforms accounted for the majority of Premium fights broadcast in the United States.

Pay Per View

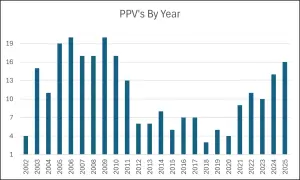

The prevalence of PPVs seems to be correlated with market consolidation. When HBO was dominating in the 2000s, PPVs were common. One reason is that HBO had enough of a market share that it was able to control prices on its own shows. But promoters (often Top Rank with Latin Fury and Pinoy Power) who couldn’t get a show onto HBO would run lesser off-label shows on established PPV infrastructure. Broadband internet was not ubiquitous at that time, and many households were still consuming television by satellite. There was pirating, but it wasn’t nearly as widespread as it is now, and the satellite providers were eager partners for shilling PPV products.

PBC’s move to broadcast networks and the subsequent competitive marketplace after 2018 came close to extinguishing PPVs. But now with the market more consolidated than it’s ever been, we’ve seen a return to heavy PPV usage. DAZN now has the same market position as HBO held and can control pricing. And its competitors are hamstrung by a lack of investment interest by any other platforms, so PBC has to rely heavily on PPVs and smaller promoters who win purse bids don’t have any other avenue for potential profit.

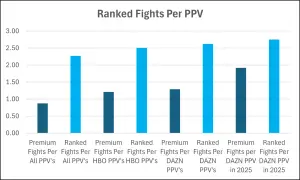

We must apologize for not being smart enough to display this information in a better format. At the far left, we see the average number of Premium and Ranked fights in all the PPVs in our entire sample, with less than 1 Premium fight and 2.3 Ranked fights per PPV. Next, we see that HBO PPVs had more premium and ranked fights than the average PPV. DAZN PPVs have been very slightly than HBO PPVs were. And on the far right side, we see DAZN PPVs in 2025, nearly 2 Premium fights per PPV, and almost 3 Ranked fights per PPV. This is the Riyadh Season effect of producing massive PPVs with stacked lineups.

This chart shows the downside to a market with few competitors. Until last year, 2005 was the year in our sample that had the highest share of Premium fights being delivered on PPV at 42%. In 2018, with three heavily invested platforms operating, just 7% of Premium fights were on PPV. But now in 2025, with the market consolidated, 58% of Premium fights were on PPV. Only 20% of the Premium fights aired in 2025 were on subscription-tier streaming platforms.

Cost Analysis

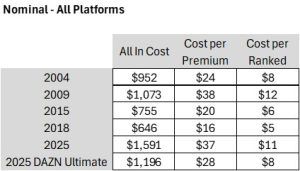

How expensive is boxing to the consumer now? And how does it compare with the rest of the years in the sample? There are several ways we can look at this, but we’ll start with an All-In cost analysis. We’ve calculated the least total cost to view all Ranked fights in a year. We added all the PPV costs to the subscription costs, but if a platform only showed 3 ranked fights in a year, we only include the monthly subscription costs necessary to see all 3 fights.

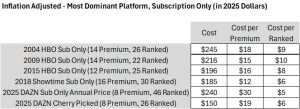

We’ve chosen the following years for comparison:

2004 – HBO’s market share peak

2009 – The year with the peak number of PPVs

2015 – PBC’s launch on broadcast networks

2018 – The height of the investment boom

2025 – DAZN’s market share peak

2025 DAZN Ultimate – An assumption of the new Ultimate pricing if it were in place during 2025

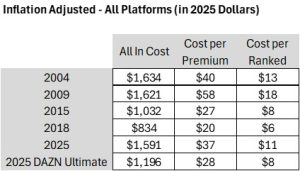

But these figures are in nominal terms; 2004 dollars are not the same as 2025 dollars. So we ran all figures through this inflation calculator for a more meaningful comparison in 2025 dollars.

The era of HBO dominance was the most expensive era by all measures. 2018, with three powerful competing platforms, was the most affordable year in the entire data set.

Now we’ll take a look at the cost of just the most dominant platform of each of these years. We’re interested in this to see how much of the total cost is a function of the dominant platform’s pricing and how much comes from the minority platforms.

And again adjusting for inflation:

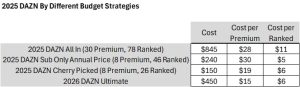

Here we can see that DAZN’s all in cost per Premium and Ranked fights in 2025 was comparable, even slightly better, than HBO’s. And the creation of the Ultimate tier creates the lowest cost per Premium and Ranked fights in the entire data set if DAZN delivers a similar fight calendar going forward. But it’s still a cost of $450, which is untenable for many boxing fans. So let’s take a look at different budget strategies that could have been used in 2025 on DAZN:

We’ve included a subscription-only package (no PPVs) at the annual price. We’ve also included a cherry-picked budget if a user only purchased the five months required to see all the Premium fights available on the platform. They would also have been able to see 26 of the 46 Ranked fights while missing out on the other 20 Ranked fights.

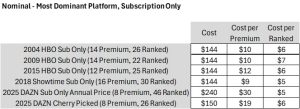

And now we will compare the subscription-only cost of the most dominant platforms in our sample:

And again adjusting for inflation:

We can see that no matter what strategy is in play at the subscription level, DAZN in 2025 delivered the highest cost per Premium fight of the data set.

What Happens Next?

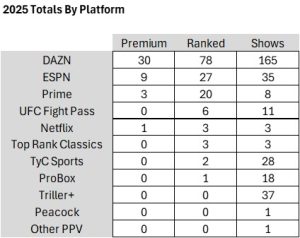

2025 marked the beginning of a new era of consolidation in the American boxing broadcast market. We have focused on Premium and Ranked fights to this point, but here is a look at total broadcasts by platform in 2025.

We should assume that UFC Fight Pass is done showing boxing, and Tom Loeffler’s stable has moved to Paramount+. We can probably assume that Peacock is done with boxing, as they’ve had plenty of opportunity the last several months to secure a deal with high-level promoters and they don’t appear to have made any effort in that direction. We also know that ESPN’s output in 2026 will likely look more like ProBox or TyC Sports without Top Rank in the fold. So it looks very likely that DAZN’s position will consolidate even further from here.

While DAZN has taken steps to deliver cost savings via the Ultimate package introduced late last year, it remains to be seen whether or not they will be inclined to deliver savings in the subscription package. If Zuffa sticks to its announced plans and truly doesn’t work with other promoters or sanctioning bodies, it doesn’t seem that DAZN will have any reason to come up with an affordable option because they won’t have any real competition.

There doesn’t seem to be any kind of bidding war for Top Rank, which has gone 6 months without being the lead promoter on a show for the first time in 46 years. Top Rank is already stocking the early part of DAZN’s 2026 schedule with its fighters without having the security of an exclusive deal. And as higher-tier Top Rank fighters become available through free agency, like Troy Isley, Zuffa may find it difficult to entice them to sign if they are forcing them to give up a future shot at a belt.

We already know that in the case of Jai Opetaia, Zuffa seems willing to ignore its stated goal and seems poised to make a fight in March to unify belts with Noel Mikaelian. Will we see more of this? If we do, it will provide much-needed competition for DAZN and may force them to consider a different strategy. And it may change things for Top Rank as well. If the threat of Zuffa locking up Top Rank fighters in free agency is strong enough, maybe DAZN would consider making a deal with Top Rank and bringing them into the fold. As it stands right now, they have no incentive to take that step.

But the reality of this situation is that 2026 should be able to deliver more Premium shows than we’ve seen in the last 25 years. DAZN has reached the same position HBO held in 2002. They can pick and choose what they want to show on their air because Prime is only mildly committed to PBC via PPVs and Paramount+ is completely committed to Zuffa. Everyone else is out in the cold, and DAZN should have the power to get fights made, though the Boots-Ortiz situation shows that there are a lot of factors to overcome.

The American market doesn’t hold the same power globally that it used to. There just aren’t many Americans watching boxing regularly. DAZN needs to have a foothold here because America and Mexico still have a lot more fighters than any other country. If there are only 300,000 – 500,000 fans watching boxing in America, is that enough for the rest of the world to cater to it? It doesn’t seem so. An increasing number of fights are happening in other parts of the world in time zones that are more conducive to the markets that have more viewers. It’s a sea change that we’ll explore in parts two and three of this article.